The rise of the Mediterranean diet

The lifestyle of labourers as a recipe for long life.

It was sixty years ago in Italy that what would become known as the “Mediterranean diet” – in Italian dieta mediterranea – was first identified as such. In Ancient Greek the word diaita means not only the abovementioned “art of living”, but also “house”, “ship’s cabin” and “research”, and thus implies that our way of eating is equivalent to our way of inhabiting the planet.

A gift from the gods

The ancient peoples of the lands surrounding the Mediterranean – that sea flanked at its narrowest point by the Pillars of Hercules (the rocky promontories on either side of the Strait of Gibraltar) – saw the Mediterranean diet first and foremost as a gift from the gods. According to ancient myth, the olive tree was a gift from Athena, the blue-eyed virgin, protector of the arts. Wheat was given to humankind by Demeter, personification of Mother Earth, whom the Greeks represented with a sheaf of wheat. Lastly, there is the vine, brought back from Asia by Dionysus, the wandering god. This divine young man, whose head is crowned with vine leaves and grapes, drank the fruit’s nectar to help him better read the future.

A pioneering couple

Oil, bread and wine: this is the Mediterranean trio that for millennia has formed the basis of the food eaten by people living in this part of the world. Nobody thought to call it the Mediterranean diet until the last century. The first to do so were the physiologist Ancel Keys, professor at the University of Minnesota (who in 1944 also invented the K Ration – a daily food ration for US soldiers) and his wife, Margaret Haney Keys, biologist at the Mayo Clinic. Pioneers in their field, they went on to revolutionise medical knowledge regarding nutrition. In 1951, the couple participated in a conference of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) in Italy. They were surprised to discover that, unlike in the United States where half the men aged between 39 and 59 suffered from cardiovascular disease, it was rare in Naples and the surrounding area. Yet nobody knew why.

The good health of rural labourers

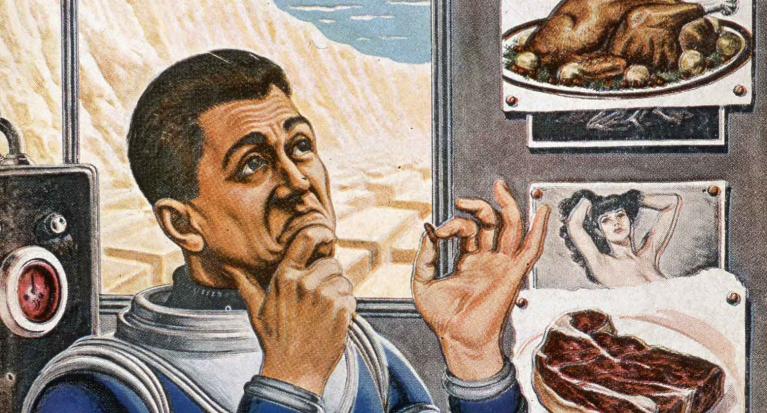

Ancel and Margaret Keys soon turned their attention to solving this scientific mystery and conducted a study on labourers from the region of Naples. Clinical analyses quickly showed that the cholesterol rates of these unskilled labourers were markedly lower than those of well-salaried office workers in the United States. The two scientists then realised that there must be a correlation between cholesterol levels and cardiovascular disease. They also had the brilliant insight that the origin of this connection lay in food. This was tantamount to their positing that, in this case, the poor eat more healthily than the rich!

By studying the labourers’ diet, the Keys learned it consisted mostly of vegetables, fruit, bread, pasta, olive oil and wine. Meat was rare, as were animal fats, that is to say, the exact opposite of the so-called Western diet.

An antidote to Western opulence

A series of international studies conducted in the countries bordering on the Mediterranean Sea validated the Keys’ hypothesis and thus furthered the reputation of the Mediterranean diet. In this period of intense research, which also saw the creation of the World Health Organisation (WHO) food pyramid, this diet presented itself as the nutritional and natural antidote to a West whose opulence was making it ill.

Frugality was the keyword

In 1959 Ancel and Margaret Keys wrote Eat Well and Stay Well, a book that became the bible for teaching the world a new dietary philosophy: frugality in abundance. They put this idea into practice themselves relocating in 1963 to the Cilento area, south of Naples: to ancient Elea, cradle of the philosophers Parmenides and Zeno. There, the two scientists fell into step with the fishermen and farmers living on the shores of Mare Nostrum so as to better uncover the secret of their remarkable life expectancy. Successfully so, as by adopting this region’s art of living for 35 years, they prolonged their own lives by some 20 years: Ancel died at 100 in 2004, followed by his wife two years later at the age of 97.

DOSSIER Trends and Turns |

| Canned food – an instrument of power | |

| The rise of the Mediterranean diet | |

| Ötzi and his diet | |

| Too much or not enough? | |

| It may look good, but is it? | |

| The perfect meal in a pill? | |

| All dossiers | |

To find out more:

VIDEO Interview with Professor Jeremiah Stamler, MD, Professor Emeritus at the University of Chicago, friend and colleague of Ancel Keys. He followed the discovery of the Mediterranean diet and today continues to promote awareness of it and adapt it to current needs. (in English)

VIDEO Interview with Delia Morinelli, who was the Keys’ cook for 35 years on the Cilento coast. (in Italian)

BOOK by Professor Elisabetta Moro dedicated to the Mediterranean diet: La dieta mediterranea. Mito e storia di uno stile di vita, Il Mulino, April 2014.

From medicalisation to patrimonialisation

Article written by Salvatore Bevilacqua which describes the registration in 2010 of the Mediterranean Diet on the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage as a historic issue of an approval process involving medicine, politics and myths about food. In French, short abstract in English....