In the land of Cockaigne

Culinary excesses, sexual pleasures, rivers of wine and the fountain of youth.

"The Fountain of Youth", 1546 (Berlin-Gemäldegalerie)" data-slide="http://www.ealimentarium.ch/sites/default/files/lucas_cranach_d._a._der_jungbrunnen_0.jpg"/>

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553)

"The Fountain of Youth", 1546 (Berlin-Gemäldegalerie)

Life in Cockaigne is full of pleasures and delights.1 Who hasn’t dreamt of the abundance to be had in this land? Of course, nowadays a wealth of food can be found on our supermarket shelves, and this myth seems somewhat outdated. But what do we really know about this imaginary land where rivers flow with wine, skies rain hot custards and plump geese roast all by themselves?

Although it may be the idea of insatiable gourmets and unquenchable gourmands that comes to mind, originally it was other pleasures – freedom, youth and sensuality – that were satisfied in Cockaigne.2 The historical context explains the myth that is, according to some historians,3 the only utopia of the Middle Ages. Cockaigne first appeared in oral accounts in the middle of the 12th century in Europe, at a time when, for all the economic and social development, food shortages had not been eradicated.

The first known text, the French Fabliau de Cocagne, dates back to around 1250.4 Fifty-eight of its 188 verses are about food, and can be seen as the dream of heavenly abundance on earth, in which hunger, and especially the fear of there being too little, are unknown. In an eternal month of May, idleness reigns and money never runs out, a fountain of rejuvenation heals and gives eternal youth, men and women indulge unrestrictedly in countless physical delights without law or morality to spoil the fun.

But while this dream was certainly geared toward tempering the harsh realities of life at the time, it was also a form of protest. Cockaigne’s gourmands were opposed to the Church in particular, but also to the new secular authorities, who advocated abstinence and fasting, and condemned the deadly sin of gluttony.5Le Fabliau de Cocagne describes a topsy-turvy world with carnival-type humour and the verses dedicated to the pleasures of eating are no exception:

Barbels, salmons and shad fish,

Are the walls of all the houses;

The beams are made of sturgeons,

The roofs of bacon,

And the fences of sausages.6

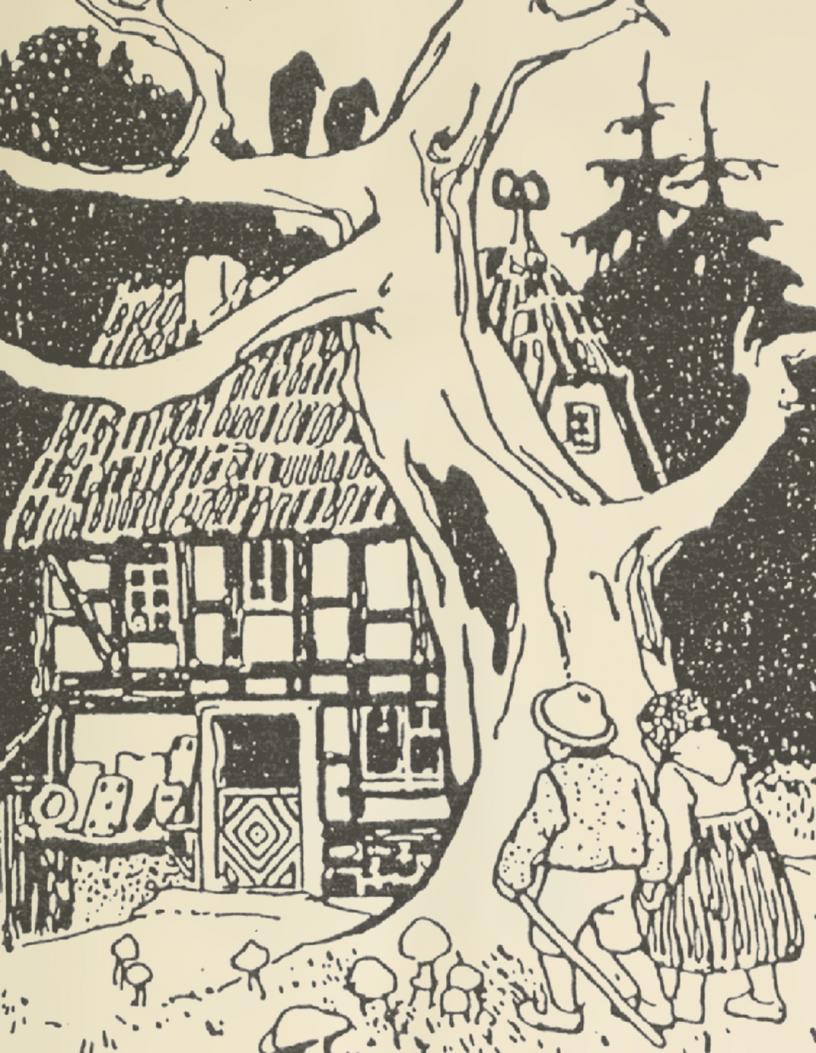

In this imaginary world, houses are edible, and an avatar with a similar type of decor reappears later in the story of Hansel and Gretel,7 in which the witch’s cottage is made of bread, or gingerbread in subsequent versions, and has windowpanes of sugar.

There is much to see in the land of delights,

For roast meats and hams

hedge the fields of wheat.

On the streets plump geese

rotate by themselves

to roast, basted

with a white garlic sauce.8

Nobody works, the more you sleep the more money you earn, and Mother Nature ensures a supply of ready-to-eat dishes. The food may be aristocratic, but also popular, whereas everyday fare, such as bread, beer, vegetables and soups are conspicuously absent from the Cockaigne diet.9 The same goes for water: only wine is drunk, and only the best:

It’s a pure and proven truth

That in this blessed land

Flows a river of wine.

Goblets appear on their own,

As do gold and silver chalices.

This river I’m talking about

Is half red wine,

The best that can be found

In Beaune and beyond the sea;

The other half is white wine,

The best and finest

That ever grew in Auxerre,

La Rochelle or Tonnerre.10

The quality of the wines is undeniable, as is that of the food, but in Cockaigne the dishes associated with noble dining are largely absent, except for a handful, such as some kinds of game. The fare here is bourgeois and rustic, with bacon, sausages and ham galore, and the other meats, fish and desserts follow recipes used for feasts and popular festivities. But rather than refinement, the main aspects of these edible delights are conviviality and abundance:12

Nobody suffers from hunger:

Three days a week it rains

A shower of hot custard

From which nobody, hairy or bald,

Turns away, I know, having seen it,

On the contrary, everybody takes what he wants.13

This myth spread throughout Europe during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, with national and regional variations. An Italian version is found in Boccaccio’s Decameron in the 14th century: “Where the vines are tied up with sausages and a goose is to be had for a farthing and a gosling into the bargain (…) there was also a mountain all of grated Parmesan cheese, whereon abode folk who did nothing but make macaroni and ravioli and cook them in capon-broth, after which they threw them down thence and whoso got most thereof had most; and that hard by ran a rivulet of vernage, the best ever was drunk, without a drop of water therein.”15

By that time, a change can already be noted, in particular that people now have to work in Cockaigne. From the 17th century, the moralists and pedagogues of the bourgeoisie appropriated the myth, making it into a children’s story condemning gluttony and laziness. The initially defiant aspect took on a moralising, didactic tone.16

Nowadays, the land of Cockaigne refers to the pleasures of food, and all the recent imagery around this theme reminds us of it. But do we still dream of it?

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553)

Erhard Schoen, 1530

Nelli, Niccolò (c. 1530 - 1576 or 1585)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1567)

Johann Baptist Homann (1664 - 1724)

Ubbelohde, Otto (1867–1922)

Oskar Herrfurth (1862-1934)

Oskar Herrfurth (1862-1934)"/>

Oskar Herrfurth (1862-1934)

Oskar Herrfurth (1862-1934)

Oskar Herrfurth (1862-1934)

Das Märchen vom Schlaraffenland.

Notes

- Cf.: Le nouveau Petit Robert de la langue française, 2010.

- Hilário Franco Júnior, Cocagne. Histoire d’un pays imaginaire, 2013, p. 7.

- In particular: Jacques Le Goff, “L’utopie médiévale: le pays de Cocagne”, in Lumière, utopies, révolutions: espérance de la démocratie: à Bronislaw Baczko, coll. Revue européenne des sciences sociales, t. XVIII, n° 85, 1989, pp. 271-286.

- This text is quoted directly from H. F. Júnior, op. cit., p. 30ff.

- H. F. Júnior, op. cit., p. 28.

- H. F. Júnior, op. cit., p. 32. All verses of the English translation of the poem have been adapted from: Paul Morris, A Vision of Cluny, Cockaigne and the Treatise of Garcia of Toledo, 2007, p. 93ff.

- Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, “Hänsel und Gretel” in Kinder- und Hausmärchen, vol. 1, 1812.

- H. F. Júnior, op. cit., p. 32.

- Ibid., p. 87ff.

- Ibid., pp. 33-34.

- Ibid., p. 98.

- Ibid., pp. 113-114 and Florent Quellier, Gourmandise: histoire d’un péché capital, 2010, p. 65.

- Ibid., p. 36.

- Giovanni Boccaccio, Decameron, 1349-1353.

- Georges Minois, L’âge d’or: Histoire de la poursuite du bonheur, 2009, p. 163; English translation from: Tales from Boccaccio, 1918, p. 39.

- Herman Pleij, Der Traum vom Schlaraffenland. Mittelalterliche Phantasie vom Vollkommenen Leben, 2000, p. 122.

Bibliography

- Hilário Franco Júnior, Cocagne. Histoire d’un pays imaginaire, 2013

- Jacques Le Goff, "L’utopie médiévale : le pays de Cocagne", in Lumière, utopies, révolutions : espérance de la démocratie, à Bronislaw Baczko, coll. Revue européenne des sciences sociales, t. XVIII, n° 85, 1989

- Georges Minois, L’âge d’or. Histoire de la poursuite du bonheur, 2009

- Massimo Montanari, La faim et l’abondance. Histoire de l’alimentation en Europe, 1995

- Herman Pleij, Der Traum vom Schlaraffenland. Mittelalterliche Phantasie vom Vollkommenen Leben, 2000

- Florent Quellier, Gourmandise, histoire d’un péché capital, 2010

DOSSIER Amazing Feasts |

| The most expensive party ever | |

| Cow tongue and venison | |

| The biggest buffet imaginable | |

| In the land of Cockaigne | |

| All dossiers | |